Learning Experience & Game Designer

About Ripley

I’m a game and learning experience designer with a brain built for structured storytelling, emergent logic, and game systems that feel as good as they function. An unrepentant multiclasser, my interdisciplinary background is in technical documentation, games-based education, theatrical direction, and program management across the sciences and arts. I specialize in crafting scaffolded tutorials, branching quests, and systemic narratives that respond meaningfully to player choice. I’m currently expanding into visual scripting and Unreal/Unity, with a growing focus on UI/UX and level design as tools for shaping player emotion, pacing, and agency. My sweet spot of inspiration is triangulated by environmental puzzle games like Myst, immersive sims like Deus Ex and System Shock, FPSs like Halo and Half Life, and RPGs like those of BioWare, Bethesda, and Cyberpunk 2077. I design for that spark of mischievous glee that comes from playing in the liminal space between outsmarting the game and breaking it, which comes from years of figuring out how to get the Warthog through doorways the designers really tried to keep me out of.

Click on the images to view design documents.

Letters of Recommendation

Table of Contents

Instructional Design & Technical Writing: Stuctured Literacy & Extensive Reading, Time Machine Math, Harvard Medical School, Pearson, curricula, staff training (selection due to IP)

Quality Assurance & Game Testing: Spiritrender

TTRPG, LARP & Escape Room Design: Anterra ~ Myst TTRPG ~ Scaffolded DnD 5e System

Game Design: Echoes ~ Catiopolis

Narrative Design & Game Writing: Apperception ~ Steam Shortage ~ Freeman, Pritchard and JARVIS in an Elevator

Design Analysis Scholarship: Queer Mechanics (Bioware) ~ Narrative Combat Design (Fightaturgy) ~ Transnational Fandom Affection (Yuri!!! on Ice)

Creative Direction & Performance: The Healing of Eowyn ~ Bootstraps ~ The Scary Question

Instructional / Curriculum Design & Technical Writing

Rethinking Leveled Literacy: Applying Extensive Reading Pedagogy to Mixed-Fluency Structured Literacy Classrooms

This professional development workshop reimagines mixed-fluency reading instruction by combining Structured Literacy with Extensive Reading pedagogy. Drawing on classroom-tested strategies from both U.S. and Japanese educational contexts, it equips ELA and ESL educators with hands-on tools: leveled vs. graded reader analysis, motivational reader interviews, reflection-based diagnostics, and sample teacher scripts. Grounded in the Science of Reading and cross-linguistic literacy research, the model applies SoR’s systematic, diagnostic, and cumulative principles to support sustained fluency, autonomy, and motivation through student-chosen texts.

Time Machine Math: A Performative, Discovery-Based Curriculum

What if our cognitive development mirrors the arc of human civilization—that we’re wired to learn math the same way it was discovered? Time Machine Math is a constructivist, arts-integrated curriculum that reorders middle and high school math to follow the historical emergence of mathematical ideas. Grounded in Realistic Mathematics Education, Guided Reinvention, and Project-Based Learning, it invites students to relive the questions that first sparked innovation—reconstructing math through performance, storytelling, and hands-on exploration. (A selection I reconstructed from a full grades 6-12 curriculum series I developed in 2003 that was adopted by two private performing arts schools.)

Placement Exam Benchmarking Algorithm (College of English Language)

Developed a data-informed algorithm for CEL’s placement exam by analyzing student performance. Also wrote and recorded entertaining listening exams.

Object-Based Instructional Design Toolkit for Digital Path CMS (Pearson)

Developed a reusable instructional object library—including interaction templates, visual tools, and layout specifications—to streamline content authoring and editorial handoff.

Action-Based Animation Glossary for Interactive Math Curriculum (Pearson)

Created a standardized glossary of animation commands and behavior logic to guide animators and math editors working in Pearson’s CMS for digital content development.

Instructional Designer's Layout & Annotation for Math Textbook (Pearson)

Digitally marked and annotated math textbook page proofs to support instructional consistency, accessibility, and layout QA across print and digital pipelines.

Medical Writing & Research Documentation (Harvard Medical School)

Edited high-stakes faculty promotion packets and research grant documents to meet compliance, scientific accuracy, and institutional formatting standards.

Faculty Credential Writing & Style Guide Compliance Editing (Harvard Medical School)

Structured academic CVs, biographical sketches, and HMS style guide-compliant submissions for medical faculty at Brigham and Women’s Hospital across departments, ensuring clarity, compliance, and professional tone.

Curriculum Backup & Deployment Protocol for Google Classroom (Youth Cinema Project)

Authored institutional backup and versioning protocol for curriculum delivery teams, integrating folder logic, tagging conventions, and real-world recovery use cases.

English Teacher Training Manual (Japan)

Developed an onboarding guide and training resource for native English-speaking instructors, covering learner-centered instruction, classroom management, and game-based learning tools.

Staff Handbook (Gymnastics Academy)

Created a comprehensive staff training resource aligned with ACA standards, covering pedagogy, emergency procedures, SafeSport Codes, and culture of play-based learning.

Family Handbook (Gymnastics Academy)

Designed a family-facing guide articulating policies, schedules, and educational goals—building transparency and trust across diverse caregiver communities.

Trauma-Informed Stage Combat Curriculum (NYU)

Authored a 4-term progressive curriculum integrating physical storytelling, intercultural pedagogy, and safety-focused consent practices for actor training. (image: Nigel Poulton’s class)

Phonics & Poetry: Rhyming and Language Play Curriculum (ESOL)

Designed a scaffolded unit combining phonics instruction and poetic wordplay to teach ESOL reading skills through rhythm, repetition, and creative literacy.

Quality Assurance & Game Testing

Spiritrender (QA Lead)

Spiritrender is a browser-based horror game built in Unreal Engine 4.23.1 (HTML5) for the two-week GameDev.js 2025 Jam, created by over 30 team members. It is a narrative-driven, single-player investigative horror game inspired by Phasmophobia and Demonologist, reimagined in a dark medieval setting with original lore, a defined player-character, and a handcrafted clue-based deduction system.

As QA Lead, I managed a team of six testers and collaborated with leads and designers across engineering, animation, sound, narrative, art, and level design to ensure system functionality, internal consistency, and narrative clarity. My responsibilities included:

Documenting bugs, test cases, and development stages to support team-wide coordination

Verifying that investigative tools provided accurate, readable feedback for player deduction

Testing edge cases involving AI behavior, navigation, and sanity-triggered events

Confirming the proper deployment of animations, sound effects, and music in-engine

Working with level and art teams to ensure puzzle clarity and visual logic

Ensuring narrative elements consistently reflected gameplay outcomes and player states

Troubleshooting browser-specific issues related to Unreal Engine’s HTML5 export

A major focus was the calibration of our sanity mechanic, the core risk-reward system. I collaborated closely with engineering to fine-tune drain and restore variables across tools, lighting conditions, and AI encounters. This system was central to the jam’s theme of balance, requiring coordinated QA to ensure it supported both strategic play and psychological tension consistent with the narrative.

In the final 48 hours, I stepped in to cover production lead duties when our producer/creative director had a last-minute emergency. I triaged features, defined a strict “must-function” list, and organized the team to ensure the game loop was stable, balanced, and playable by the submission deadline.

While not all final assets and updates were implemented by the jam deadline, we plan to polish and re-release the game with our finished art, expanded clue logic, updated UI, and additional environmental feedback systems.

TTRPG, LARP & Escape Room Design

Anterra: 6 Simultaneous Escape Rooms

Article published in the AATE (American Alliance for Theatre & Education) online journal, ElevAATE: Perspectives in Theatre & Education.

Role: Narrative Systems Designer, Worldbuilder, Puzzle Designer, Live Game Director

Format: Live Action Roleplay (LARP) • Escape Room • English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) players

Anterra is a live-action narrative experience built to simulate high-stakes teamwork under pressure. Set on a colonized planet experiencing a solar flare crisis, players take on specialized roles in a modular base where communication, critical thinking, and inter-team coordination determine survival outcomes. This game was run as our Thanksgiving Event in my role as Education Director at the Santa Monica College of English Language, with the pedagogical goal of encouraging as much English use as possible. Given the driven pace of the story, this also required logistical arrangement of each team to avoid common native languages and stragetic deployment of advanced speakers to provide support for emergent ones. Team selection also took into account students’ puzzle type preferences.

Designed for multilingual players of mixed experience levels, Anterra blends the jigsaw cooperative learning strategy with branching narrative, asymmetric role mechanics, and embedded logic puzzles inspired by real-world STEM challenges. Players must decrypt transmissions, interpret maps, assemble devices, manage finite resources, and weigh ethical dilemmas in a ticking-clock scenario with dynamic consequences.

I did the narrative system design, writing lore and mission scripting, creating flexible station mechanics, and designing for emergent team behavior within a structured narrative arc. In addition, I designed all the puzzles, with the assistance of my usual collaborator on TTRPG campaigns, Alec Grey. Game balance accounted for real-time player adaptability, scaffolded communication difficulty, and cross-role dependencies to simulate both crisis response and bureaucratic breakdown.

Logistics:

As I was running this game for 70 students effectively solo (teachers were given simple instructions to monitor their escape room only), I recorded synchronized videos that were started in all classrooms simultaneously. In these videos, I performed the role of game master as mission control, directing them to move throughout the school at specific times, giving them their directives for both the overall game and the individual puzzles, and kept them on track with a timer and other “station-wide” events. Therefore, the beginning and end of the videos were the same in every room, but the middle segment was specific to the escape room set in that classroom. Then, during the game, I was free to move between each escape room to provide hints and narrative urgency.

Takeaway:

Anterra proves that serious games can be high-agency, high-emotion, and high-strategy—bridging environmental storytelling, player-led pacing, and narrative consequence into a single embodied system. Students spoke excitedly about this event for months afterwards and I’ve been told it is one of their best memories of being an international student.

Game Introduction

Played the day before. Character sheets handed out.

Game Start

6 classrooms that double as team and job stations. To get an accurate idea of gameplay, play each of the videos at the following times, where there is unique content in each room:

The first 6:54 are the same in all rooms. This has them move from their normal classes (fluency level) to their team rooms and introduce themselves in character.

At 6:54 their time is interrupted with a red alert! They are given deployment instructions to their job stations and time to travel.

At 9:34 they are in their job stations and receive the specific instructions for their escape room puzzle and the information they must bring back to their teams to survive the solar flare. Additionally, at 11:33, the Magnetic Shield Control Room experiences a yellow alert as the blast shield bulkheads are deployed for an additional level of challenge.

At 52:48 the job stations are over and they return to the team rooms to share their answers from the puzzles to determine the correct shelter location.

At 1:07:30 they must make their final decision on where the safest location is on their maps. The solar flare hits and the correct answers to the puzzles are revealed.

At 1:09:10 I somehow manage to tie this space opera back into a Thanksgiving celebration, and they go eat a buffet!

A reimagining of the Myst universe built for tabletop play for middle to high schoolers as a summer camp. This project expands the original lore into a multiverse of unstable Ages, corrupted ink, and ancestral conflict. Players explore fragmented realities created by Atrus, Kathri, and their children—each with distinct puzzles, environmental storytelling, and narrative stakes. I created custom backgrounds, classes and species in D&D 5e which enabled students to learn about literature concepts like genre, tropes, and plot structure through their character’s meta-savvy perspective. Designed to evoke the feeling of outsmarting the system while operating within carefully crafted logic bounds, the game blends exploration, choice-based narrative, and layered mechanics in a modular campaign structure.

Myst-Inspired Narrative Puzzle TTRPG

Scaffolded D&D 5e handbook for Kids

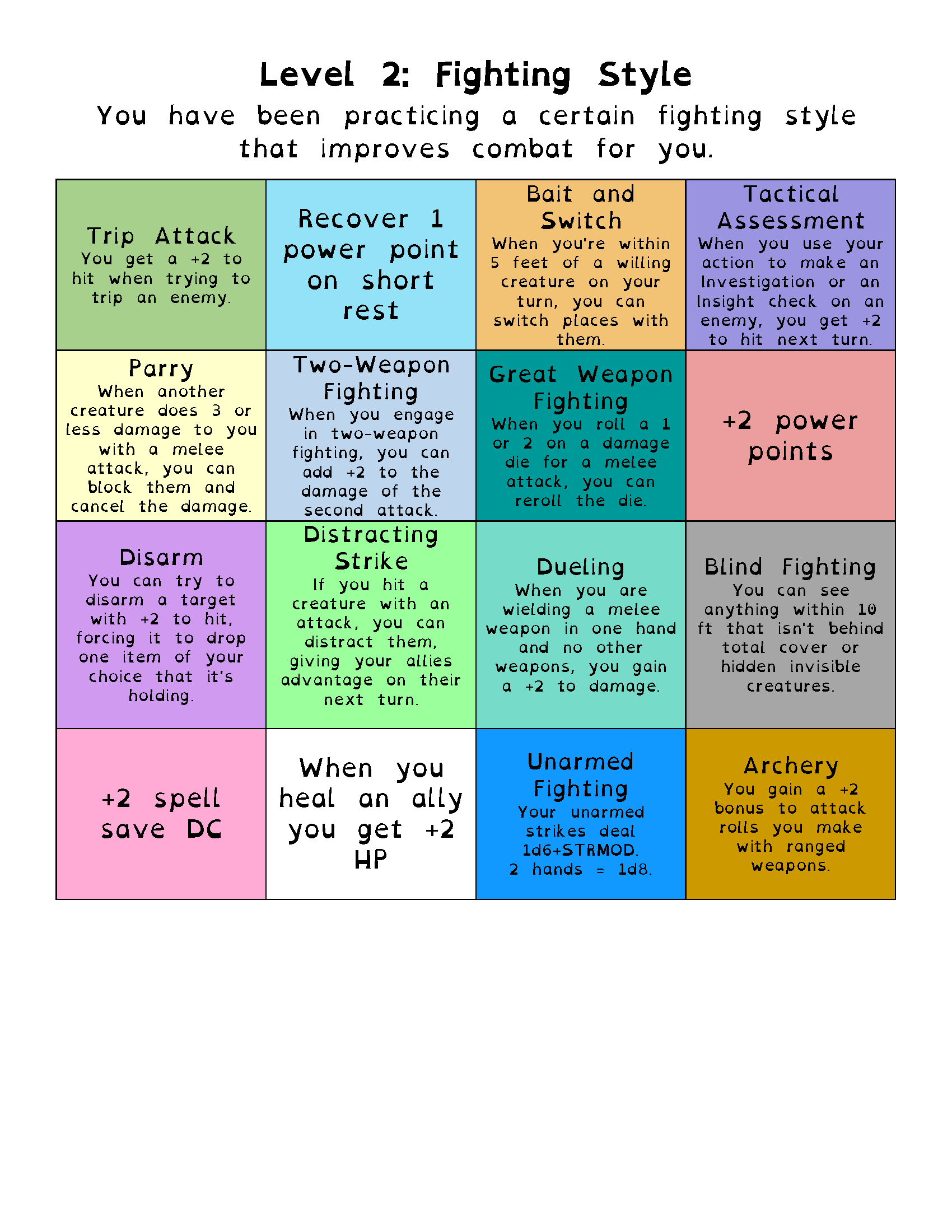

For younger players (ages 5-12) I and my collaborator, Alec Grey, analyzed the action economy and features of D&D 5e through the lens of developmental learning and cognitive load. Our goal was to introduce the rules of D&D as the character leveled in order for it to be more manageable for kids. This allowed them to have practice with a limited set of rules for a time and then get the excitement of their character having totally new abilities (bonus actions feel like they can now do 2 things every turn). This adjustment revealed a lot of complicated balancing issues between class progressions and species features. Since I was DMing for mostly 5-6 year-olds during its development, I wanted to avoid outcries about unfairness. I decided to allow every character the same feature types. So everyone got a fighting style, spells, a feat, a bonus action, a reaction, etc. Additionally, I built out a selection of subclasses as full class builds (16 total) to give players a sense of special uniqueness. I enjoyed this creative headache of breaking down so many aspects of 5e (including UA content) and determining the most interesting, engaging and fun aspects and then balancing them as well as possible. Click here for PDF.

Game Design

Echoes

Non-Linear Narrative Game Design

Echoes is a nonlinear narrative puzzle game in which players investigate sonic anomalies using a multi-mode analysis tool (SEAK) to uncover a dimensional mystery, solving immersive audio-based puzzles and assembling fragmented storylines through a Lock & Key progression system inspired by Myst and supported by deep sound-world mechanics.

CATIOPOLIS

Hybrid Genre Game Design

Catiopolis is a cooperative narrative sim where players design physics-driven catios a la Coasterworks and train AI cat squads through Myst-style puzzles and XCOM-inspired tactics to fulfill increasingly surreal, mission-based objectives.

Narrative Design & Game Writing

Apperception: The Paradigm Shift

Narrative Systems Trigger List

For this week-long Beginner’s Game Jam, I designed the entire narrative system, including puzzle logic for scripting, dialogue triggers, and cutscene structure, recorded and edited all VO audio, and created a cinematic sequence to replace missing art assets—delivering a fully scoped narrative package ready for integration. The game’s emotional throughline was inspired by Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), with color-coded dialogue text representing the internal voices of Emotion Mind, Reasonable Mind, and Wise Mind. The project was unfinished due to time management difficulties, as they often are. Dialogue written by jam collaborator, but dialogue functions designed by me.

Twine Game: Steam Shortage

Writing Test Prompt: Our hero feels they will die in five minutes if they do not get a glass of water. Steam Shortage is a short Twine narrative game about mechanical crisis, scientific pride, and the emotional pressure that builds when professional stakes collide with personal ones. A steampunk crisis of etiquette, engineering, and eros. Twelve minutes to stop a dirigible meltdown. A lifetime of invention on the line. And someone you never expected behind the counter.

The Machine Age has blanketed London in soot and steam, but you’ve been exiled to the lonely countryside with only correspondence from a mysterious supporter as your companion. Finally, your collaboration has born fruit and your triumphant return is guaranteed, until a critical malfunction risks your greatest invention yet. If the orichalcum core destabilizes, you lose not only your life’s work, but your last chance at redemption with the Royal Society.

Now grounded in Fleet Street with no water, no time, and no social grace, your only hope lies in the bustling chaos of a coffeehouse... and the green-eyed waiter who seems oddly familiar.

Victorian steampunk setting with richly textured prose

Time-sensitive decisions and branching narrative paths

Slow-burn queer romance or professional partnership routes

A mix of science, myth, and social satire

Multiple endings shaped by your choices, decorum, and daring

Will you save your ship, your reputation, and maybe something even more fragile?

Cutscene & Quest/Level Design

SHIELD Elevator Trouble (Half-Life x Deus Ex x MCU)

Writing Test Prompt: Three IP Characters Caught in an Elevator

Wrote and designed a cutscene within a game concept featuring Freeman, Pritchard, and JARVIS as low-priority SHIELD agents navigating a botched mission. Focused on character-driven banter, layered friction, and integrating stealth/combat mechanics into a narrative arc. I gave Freeman a voice (based on fan playstyles), matched tone across IPs without flattening them, and built in humor, tension, and just enough vents.

Design Analysis Scholarship

Designing Queer Choice Systems: Playersexuality, Erasure, and Inclusive Romance in BioWare RPGs

This essay explores how BioWare’s groundbreaking romance systems helped define queer storytelling in RPGs, while also revealing patterns of unintended erasure—particularly of bisexual and trans identities—through playersexuality. The analysis investigates how NPCs' attraction systems, dialogue gating, and lack of intra-NPC queer expression flatten queerness into conditional player responsiveness. Rather than critique from the outside, the piece is written in admiration of BioWare’s legacy, offering constructive insights on how to evolve choice-driven romance mechanics into richer systems of identity, queerness, and narrative agency.

Combat Systems and Fightaturgy: Choreography and Embodied Narrative Design

This paper reframes stage combat as a design system for storytelling, drawing connections between theatrical fight choreography and combat mechanics in games. Through analysis of fight training culture, safety constraints, and movement vocabulary, it explores how physical action can express character psychology, narrative structure, and world-specific logic. Bridging martial arts codes and dramatic stakes, the paper offers a framework for designing combat systems that prioritize both mechanical clarity and narrative embodiment, helping players experience fights not just as challenges—but as moments of emotional and story-driven consequence.

Fandom, Affection, and Soft Power: What Global Queer Communities Teach Us About Player Engagement

Using Yuri!!! on Ice as a case study, this paper analyzes how queer fan communities engage with media through affection rather than imperialist yearning—building transnational ecosystems of cultural meaning, visibility, and narrative co-creation. Applying these dynamics to game design, it argues that understanding fan labor, emotional attachment, and soft power can help studios create more resonant, socially powerful worlds. The piece reframes fandom not as passive consumption, but as a system of affective design response—something games can invite, reward, and learn from.

Creative Direction and Performance

The Healing of Eowyn

Created during Covid, a devised film exploring the narrative arc of Tolkien’s character Eowyn, deconstructed using jazz and martial arts to explore themes of ableism and gender identity. I arranged Tolkien’s writings into a script, directed 29 Voice Over artists, sang the jazz standards Lush Life and Sophisticated Lady, and performed the physical acting. Edited in Premiere Pro.

Bootstraps

A collaboratively devised science fiction film exploring themes of (dis)connection across time and space, inspired by experiences of Covid. I co-wrote, performed, and edited in Premiere Pro. Uses soundtracks from Halo and Skyrim. See credits for collaborators.

The Scary Question

A short skit turned radio play due to Covid. I directed and edited in Audacity, performed by two high school students in the NYU Youth Ensemble.